On Writing Testament

by Nino Ricci

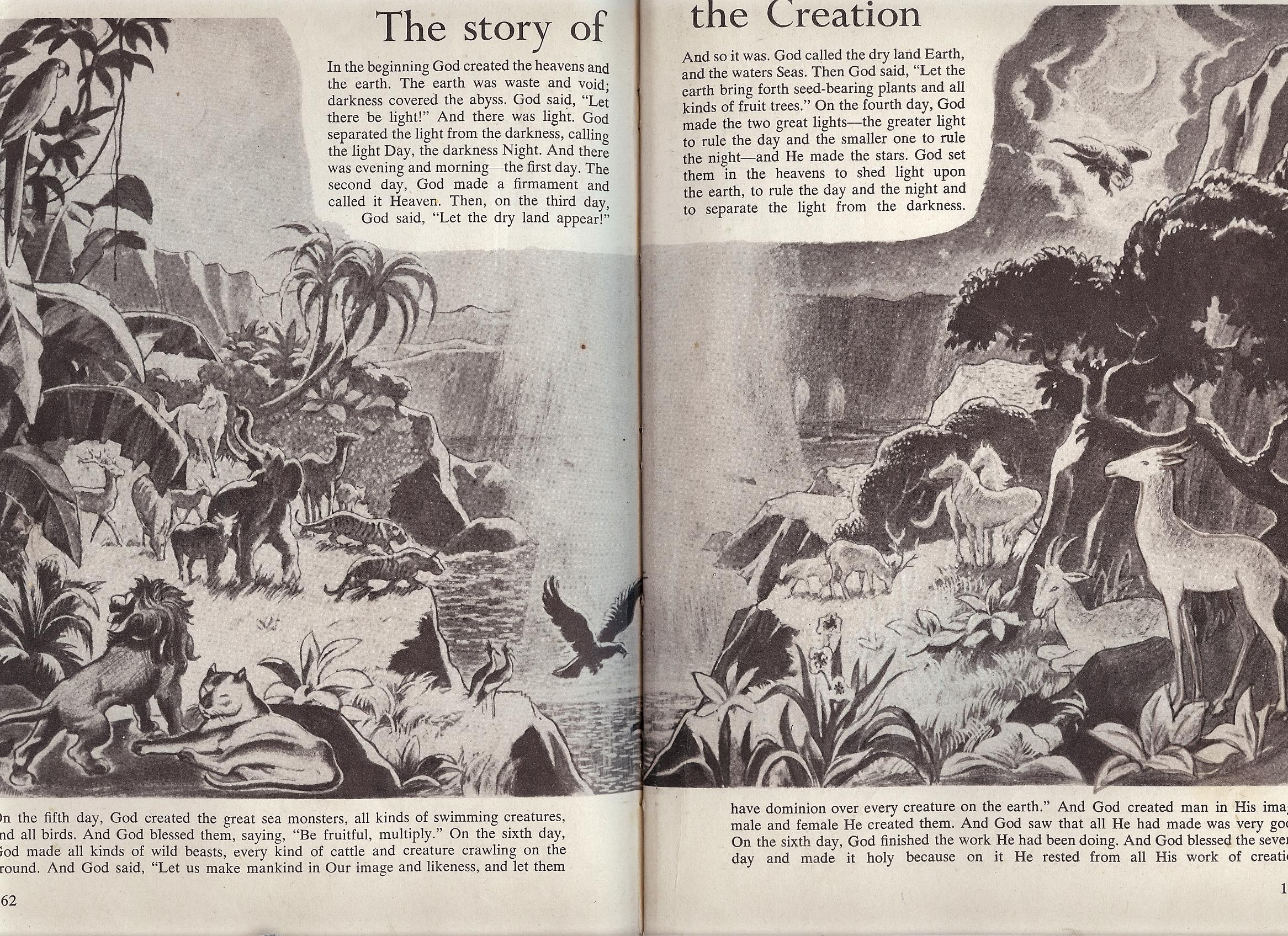

The original seed of inspiration for my novel Testament probably goes back to the first book I ever owned, a picture bible called The Guiding Light that was presented to new-borns in my hometown by our local hospital. The gentle, light-bathed Jesus depicted there became my first hero, and its stories of lepers and sinners and miracles the backdrop to my imagination. As I grew older, that first untroubled relationship I had with Christianity gave way to a thornier, more conflicted one that saw me pass from post-Vatican II Catholicism to born-again evangelism and finally to a last, desperate phase with Dale Carnegie and Norman Vincent Peale. But though by early adulthood I could no longer have properly called myself a Christian, neither, by any means, could I say I’d got free of Jesus, who seemed far too powerful a figure to rid oneself of by so simple a thing as a loss of faith.

By my university years I had found the way of holding to Jesus by reinventing him, seeing him no longer as a figure of faith but of history, on the one hand, and of myth, on the other. What in my youth had seemed the impenetrable, God-delivered arcana of the priests and nuns, the gospels of the New Testament, now revealed themselves as patchwork texts written by real people in a real time and place, and showing ample evidence of their human composition—in their divergent, often contradictory points of view; in their many gaps and anachronisms and evidences of editorial tinkering; and in the vital, radical, and frequently difficult Jesus that nonetheless shone through in them, one considerably at odds with the sanitized version of him that I’d tended to get through the church. What emerged from this re-envisioning of Christian tradition for me was a double sense of Jesus, as a real figure of vitality and brilliance and contradiction onto whom had been overlaid, however, a mythic Jesus of apocalypse and divinity, who in the pattern of death and rebirth relived every ancient fertility myth from the stories of Thammuz and Marduk of ancient Sumeria and Babylonia to the Egyptian Osiris and the Orpheus and Adonis of the Greeks.

The notion of a fictional treatment of the life of Jesus had already begun to take shape in my head by that point, as the logical convergence, it seemed, of my own personal obsession with the figure and my continually deepening understanding of his wider cultural importance. Like a magpie I began to gather up bits of lore and fact on the subject as they came across my path and to acquaint myself, in a fairly unsystematic way, with the vast array of Jesus retellings, from Ernest Renan’s La Vie de Jésus, a groundbreaking if somewhat florid 19th century attempt at a re-imagining of Jesus, through to Jesus Christ Superstar. What I found, however, was that few of these treatments, for all the radicalness they may have had in their own time, were quite able to shed the mantle of divinity that cloaked the traditional Jesus. Yet it seemed to me a more interesting Jesus would be an entirely human one, whose power as a spiritual leader and whose resonance into our own day could not be explained away by divine intervention.

When I finally came to begin my own novel, some twenty-odd years after my first conception of it and via the detour of a trilogy of somewhat more autobiographical works, I set about to do my research in a slightly more ordered manner, first trying to ground myself in the current state of biblical scholarship. For all the contentiousness and territoriality that I quickly discovered was the general rule among New Testament scholars, I found that on purely textual issues there was in fact a fair amount of consensus among them. Most agreed, for instance, that the first gospel to be written was that of Mark, probably, based on internal evidence, just after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple by the Romans in 70 CE. Scholars also tended to agree that both Matthew and Luke had derived much of their material from Mark—hence the classing of the three as the ‘synoptic’ or ‘seen together’ gospels—as well as from a conjectured second document that scholars had dubbed Q, from the German Quelle, or ‘source.’ Q, scholars surmised, was probably an early collection of the sayings of Jesus unadorned with any narrative elements, not unlike a text unearthed in Egypt in 1945, the Gospel of Thomas, a collection of 114 sayings of Jesus which some scholars dated as early as the 50s CE, others rather later. The final canonical gospel, that of John, was apparently somewhat more controversial—it was almost surely the last gospel to be written, and possibly the work of several hands, but showed quirky evidences here and there of a firmer grounding in historical truth than the others, giving some credence to the theory that it had its source in John the apostle.

It was exactly on the question of historical truth, however, that all consensus among commentators seemed to break down. On one hand I found someone like New Testament scholar Burton Mack, who in his book Who Wrote the New Testament? argued that the gospels were essentially works of propaganda composed according to literary conventions of the time, and who dismissed as futile any attempt to get back through them to a ‘true’ historical Jesus. That the earliest surviving writings of the Jesus tradition, the letters of Paul, did not contain any significant details of the life of Jesus, nor, apparently, did the hypothetical sayings gospel Q, seemed in some sense to lend support to Mack’s view, suggesting that the narrative aspects of the gospels were used to flesh out and make more attractive to followers an earlier tradition that put no emphasis on Jesus’ life history. At the other extreme, however, I found southern American writer Reynolds Price, whose interest in Jesus had led to a life-long study of the New Testament and to his best-seller Three Gospels, which included personal translations from the Greek of Mark and John as well as his own ‘apocryphal’ gospel blending the original four. In contrast to Mack, Price argued that the gospels stood entirely outside and above any of the literary genres of their day, and he found incredible the notion that works of such originality and ‘life-transforming urgency’ could be anything other than honest attempts to render the real events of a real life. In support of Price’s claim was the fact that the gospel tradition had established itself relatively quickly, within sixty years of Jesus’s death, and among a group that was largely poor and isolated and under threat and that would hardly have been in a position for sophisticated efforts at propaganda.

Unfortunately, I discovered, there were few sources to turn to outside of the gospels for any independent verification of their claims. Indeed it seemed that practically the only other surviving record of any note from that part of the world that was more or less contemporary with the life of Jesus was that of the Jewish historian Josephus, who was born around the time of Jesus’s death. Josephus proved very useful in helping me to understand the political and cultural ferment of Palestine in the first century—a place of many sects, from the Pharisees to the Essenes, of many political movements, mainly aimed at the overthrow of the Roman occupiers, and of many messianic figures, who periodically amassed large followings before, as usually happened, being murdered by the Romans or their client kings. He also painted for me a compelling portrait of how these various social currents, along with the increasing brutality and corruption of the Roman regime, led to the disastrous Jewish war of 67-70 AD, in which the Jews were utterly defeated and their temple destroyed. On the specific subject of Jesus, however, Josephus was not especially forthcoming: the sum of his commentary on him, once the ham-fisted interpolations of later Christian editors had been accounted for, added up to no more than a few lines, portraying him as a wise man who performed many ‘startling feats,’ won many followers, and was crucified by Pontius Pilate, for what reason Josephus didn’t make clear. ‘And the clan of Christians,’ Josephus concluded, as if speaking of some brave but ultimately minor and forgettable sect, ‘has not died out to this day.’

How, then, to make one’s way among these widely diverging perspectives—the historian at one end who had accorded Jesus no more than a few passing lines, the devotees at the other who had made him a god, and then the modern commentators fighting over all the territory in between. In the end, I chose the middle course, assuming that a tradition as evocative as that of the gospels could not have arisen out of nothing but also that the truth claims of the gospels had to be taken in the light of their own inconsistencies and their clearly proselytizing intent. In following this course I was helped by a great range of New Testament experts, from people like Father Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, whose guide to the Holy Land provided me a rigorous archeological introduction to the world of Jesus, to people like Reynolds Price and British writer A.N. Wilson, who seemed to come to the subject of Jesus, not unlike myself, from the point of view of personal passion, to the extensive work of the Jesus Seminar, which since the mid-1980s had striven to separate the Jesus of history from the Jesus of myth. Using detailed criteria of textual analysis and of cultural and historical contextualizing, the Jesus Seminar had worked to determine which teachings in the gospel tradition could realistically be traced back to Jesus and which were likely later interpolations, their results published in the book The Five Gospels, which provided original translations of Mark, Matthew, Luke, John, and Thomas along with commentary on each of the utterances attributed to Jesus. The Jesus Seminar helped provide me with a map for making my way through the minefield of Jesus studies, applying reason, methodology and a spirit of critical enquiry—though I found they had no shortage of critics and detractors—to a field too often marked by dogma and irrationality.

In the many cases, however, where there was no clear guide, I let myself be led by instinct, imagination, and my own intuitive sense of what might best shed light on the character of my protagonist. I was aware, for instance, of an early, possibly rabbinic tradition—cited in the 2nd century by the Platonist Celsus in his True Discourse, an argument against Christianity—that Jesus was the bastard son of a Roman soldier. The standard view of Christians, of course, had always been that the story was simply a fabrication intended to discredit them. Yet given that the issue of Jesus’ paternity was a central one in Christian thought, it seemed at least possible that there was more to the matter. Indeed, it was the gospels themselves that raised the issue of Jesus’ bastardy: in the Gospel of Matthew, Joseph, on hearing of Mary’s pregnancy, at once assumes she is disgraced and decides quietly to break off with her, changing his mind only at the urging of the angel who visits him. Certainly, then, there was a way to read the tradition in which the virgin birth, and its pre-empting of any question of paternity, could be seen as an attempt to overcome some irksome aspect of Jesus’ conception such as illegitimacy. Once I’d started thinking in those terms, I began to see a new way of understanding Jesus’ teachings—his privileging of the marginalized, his defiance of convention, his emphasis on the inner person rather than on the outward forms of religious observance.

Similarly, where there were great gaps in the tradition—almost nothing is said in the gospels about Jesus’ youth and early adulthood, for instance—I usually simply took a creative leap in the direction that seemed most likely to bear fruit. My Jesus, in line with another somewhat renegade hypotheis, spends a good part of his childhood in Alexandria. Again, it is the gospels that provide some basis for such a notion, with their story of the flight into Egypt; while Celsus, for his part, claims Jesus, ‘on account of his poverty, was hired out’ to Egypt, where he acquired certain magical powers on the strength of which, when he returned home, he ‘gave himself out to be a god.’ In the modern era, there has been a good deal of speculation that Jesus may have spent time in Alexandria, based on similarities between his views and those of the Greeks. In fact, Jesus likely need have gone no further than Galilee to get exposure to Greek views, as there were a number of cities in the area, one only three miles from Nazareth, that were essentially Greek, leftovers of the Hellenizing period that had followed the conquest of the region by Alexander the Great. But the Alexandrian setting seemed to me both plausible and suggestive, providing for an exposure not only to Greek philosophy but to a cosmopolitan culture that in that era would have been one of the most diverse, progressive, and vital in the world.

Albert Schweitzer, in reviewing back in 1906 the already extensive literature devoted by then to the quest for the historical Jesus, made the point that people tended find the Jesus they were looking for, each epoch and each individual recreating him in their own image. Certainly the Jesus I came to in the end—a man of contradiction and ambiguity, capable of great wisdom but also of arrogance, a man of peace who was yet perpetually combatative—seemed at times too contemporary in his struggles and too relevant to our own era in many of his concerns. Yet coming to the subject from the point of view of a non-believer, I had initially suspected I might emerge with a very different portrait, of the sort of deluded, megalomaniacal cult leader common enough not only in our own day but in that of first century Palestine. That was not the Jesus I ended up with. Instead there seemed, in sifting through the bits and fragments that had come down to us and in piecing together what could have been, the possibility of a Jesus who was entirely human yet visionary, revolutionary and radical in his thought, and who indeed added something new to the world that continued to have relevance to this day. To find this Jesus I often did not have to go much further than the gospels, though reading them, admittedly, with a fairly critical eye and with a much fuller sense of the social, political, and cultural context of the time than they themselves provide. And if such a Jesus in the end seemed a more relevant and living presence than I had anticipated, then a great part of that, I felt, had exactly to do with the very complexity and ambiguity at the heart of the Jesus tradition, and that seemed to me the best argument of the rootedness of that tradition in a real man of flesh and blood.

© 2003 Nino Ricci. Reproduction or use without the author’s written consent is prohibited by law.